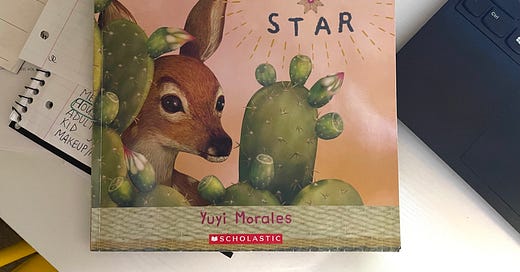

Recently, I was sitting on the edge of my seven-year-old’s bed reading the book Bright Star by Yuyi Morales. It’s the story of a newborn fawn in the in desert of the American Southwest. An invisible narrator assures the fawn of love, encourages her to explore, and coaches her through what to do when threatened. At one point the fawn encounters a tall, gray wall enmeshed in barbed wire, a stark contrast to the desert life around.

“When you feel afraid and begin to hurt inside,” the narrator says, “Let it out! Shout it loud! Let the world know how you feel!”

Taking the advice, the fawn looks at the wall, approaches it, and bellows a huge “NO!” with letters that fill up the page.

At this point, in real life, two things are happening.

1- I am silently fretting that this page is teaching improper behavior, my inner dialogue sounding something like, “I want my kids to be comfortable expressing emotion, but isn’t this a step too far? They’ve got to have some self-control! It’s a fruit of the Spirit!”

2- My daughter is asking, “Why is the deer yelling at the wall?” I am too distracted by my ethical dilemma to answer her question, “I’m not sure what that wall is” I tell her. So, we continue reading.

At the end of the book there were a couple pages explaining the background of the story and how it came to be. My heart squeezed when I read these words,

“I made this book knowing that children everywhere, but especially migrant children at the borderlands, have experienced things that they should not have to endure. I began writing Bright Star…and saw how people, sometimes walking in caravans, reached the border with the hope of entering the United States… Few were able to enter, and when they did, often crossing the border at places like the one you see in this book, they were detained. Families were separated and many adults were sent back to their countries of origin without their children. It is possible you saw this too. It is possible you were one of those children.” (Yuri Morales, Bright Star)

The story’s cement wall represented the wall between the US and Mexico; I cringed with how obvious this should have been. We flipped back to that page and revisited the wall’s true meaning. My daughter interjected that she knew all about it because they had talked about it in school. I accepted her hyperbole.

Long after she skipped away, attention expired, I sat with that book in my hands. What had drawn my focus to the presence of “problematic” behavior in the story? Why did I only see that piece of it when something much deeper was going on?

I already knew the answer: it was the straightforward privilege of living as a non-oppressed person. My family is safe, we don’t have to advocate for survival, we have everything we need right here in our home. We have the luxury of prioritizing non-essential things like “appropriate” behavior. I can read a book and be uncomfortable about a deer lacking self-control before I realize that the deer is a metaphor for the plight of the oppressed.

I’ve kept this book out on my desk, the fawn’s gaze reminding me of the fear, danger, hunger, and suffering going on at this very moment, south of my northern home, but also in my northern home. I move these thoughts to the front of my mind, a gesture of rearranging my focus to make justice and compassion the lens for interpreting life.

My privilege lens tends to orient me towards inward purity rather than outward compassion. It’s a lens that I’m aware of; it’s a lens that I successfully shatter at times. But it’s still there. And this is why I read to myself and to my kids. We need discipleship in seeing others first and not being blinded by our own problems and trials. I want to be attentive to hearing God’s voice in all the small spaces. Especially ones as small as children’s stories.

I appreciate your authentic reflections on a very real moment of encounter, confrontation, and transformation all tied up in something as simple and quotidian as reading a book to your child. Your meekness in being able to admit your "blindspot" and openness to the heart of God for the oppressed is instructive for us all.

What a profound reflection. Thank you for sharing so vulnerably, Crisanne.